Embracing Tango

It seems to me that most of the milongueros in the videos have their partners slightly to their right as they face each other. It looks like the right side of his chest is closer to her left breast than the left part of is chest to her right breast, thus creating an impression of openness or "V" on the leader's left side. I guess that this is what is referred to as the open/close side of the embrace. What do you think? I'd love some information to help me decipher this part of the embrace. This seems like an easier way to dance instead of standing "chest to chest" in a flat line.

Also, who takes the lead in determining what the embrace is going to be? I have heard seemingly contradictory opinions, such as the follower determines the embrace, and others state that the leader should. Please let me know if I missed the part where you address this issue.

Nice question. Discussions about different styles of embraces, like the “V-style embrace” vs. the "front-to-front milonguero embrace", or "close embrace" vs. the "apilado embrace" are popular topics in workshops and Internet discussion groups—but I think it’s mostly nonsense. People in the milongas aren't interested in displaying different "styles". For social dancers, there's only good technique, or bad technique. Good technique is what lets you function efficiently, and bad technique is what doesn’t. Thousands and thousands of accomplished dancers go out every day in BsAs, and they want to connect quickly and dance. Nobody wants to fool around with imaginary embraces—so let's take a look at how it works in the real world.

The first thing is to have the right posture (you can review it on pages 5 and 6 of this chapter). Now imagine two people standing face to face with their weight far enough forward that they can come together and connect comfortably at the chest. The first myth to dispel is that there is an "apilado style", where couples lean radically into each other. It doesn't happen. Couples generally stay forward just enough to maintain a sufficient chest connection (or in some cases stomach connection) for leading and following. The chest pressure can vary, but it's usually about as much pressure as placing your palms together, like praying. The feet are just far enough apart to allow the partners to step across the inside of the embrace without kicking each other.

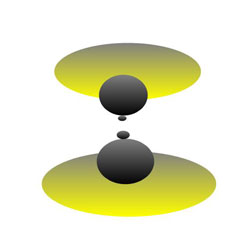

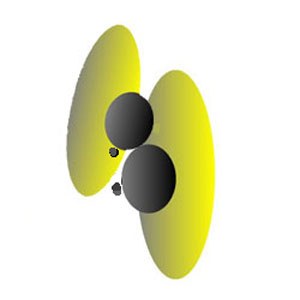

The second myth is that there is a front-to-front, or button-to-button "milonguero" embrace. If you look at the first picture below, you'll see it doesn't work—unless you also want to have a nose-to-nose, and mouth-to-mouth embrace.

The left figure shows that you can't embrace straight on without bumping noses.

You need to move about six inches to the side to make it work (right figure).

The picture on the right shows that the partners need to move to the side a little to make the embrace work. How far? Depends on how fat your head is, but about six inches should do it. You need just enough offset to allow the heads to slide in next to each other, cheek to cheek. (The man is the bigger figure at the bottom.)

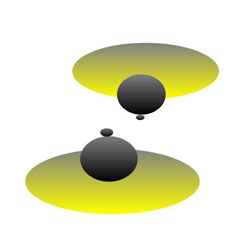

So you've shuffled a bit to the left, and you're standing there chatting. But sooner or later, you run out of small talk... and when the couples around you begin dancing and drifting in closer and closer, it's time to go. The man usually makes the first move by taking a very small step forward, or maybe just leaning in a little. This is the signal for the woman to do the same. As they move together, he reaches around her back with his right arm, and pulls her in gently. She tips forward slightly, and lays her left arm over his shoulders. (Or she can place her hand on his upper arm or shoulder, if she wants.) At the same time, his left arm comes up, and she raises her right arm to take his hand. (For examples of arm and hand positions, see pages 2 and 3). That's all there is to it... but look at what happens:

As the couple comes together, the woman will naturally turn at a slight angle

to her partner, as she as she presses against the side of his chest.

Notice that as the partners come together in the embrace, the woman's body naturally turns a little. That's because she's offset to the side, so the center of her chest naturally comes against the part of her partner's chest that curves away. Her breastbone ends up more or less on her partner's right breast. This small, natural angle isn't caused by the arms. It results from the way the torsos come together—although it does help the arms a little, by making it easier for the couple to reach around and embrace on the closed side. And it's a bit easier on the open side as well, because the partners don't have to hold their arms back, away from each other quite as much to clasp hands.

If you look back through the videos and pictures on this site, you should see that almost everyone uses this natural, efficient embrace. To me, this is just another example of the way the fundamental techniques of tango have evolved over time into the most efficient way for people to get together and express the music.

Variations

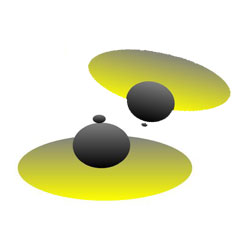

One variation is for the woman to turn her head to the right, so her left cheek is against the man. This normally doesn't affect the rest of the embrace, although it may turn the woman slightly to her right, and cause a small increase in the angle between the partners. To show it, I simply took the picture above and photoshopped the noses into different positions, without changing the angle of the bodies. In the photo on the right, Napo and Lili show how it looks in a milonga:

A variation: The woman can turn her head to the right, so her left cheek is against the man.

Napo and Lili dance very comfortably like this all the time, without affecting the rest of the embrace.

This woman's left cheek to man's right cheek embrace works fine if the angle between the partners remains small—but when you begin to increase the angle, as Paiva and his partner do on the last page, a couple of bad things happen. One is that it becomes almost impossible to walk forward in-line. The couple is restricted to having the man walk forward along the woman's right side—or to staying in one spot, separating, and doing figures in place (i.e. show tango). An even bigger problem is that whenever the man moves forward, the woman is forced to walk at an angle. Alej and I have experimented with it, and she finds it very uncomfortable. The figure below demonstrates why. The woman must step back asymmetrically, and as the image shows, stepping with the left leg is especially difficult. As the man moves directly forward, she must twist at the waist, and reach back and around with her left leg to take the step. It can be done... but why?

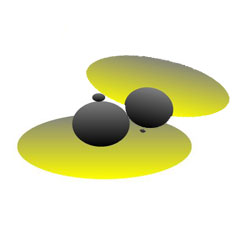

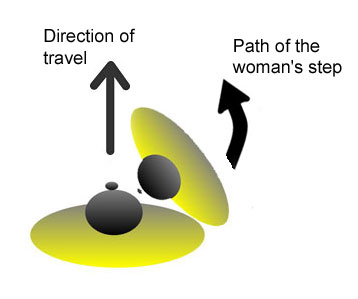

Victims of Fashion: Notice the path the woman's left foot must take as she walks back.

The large angle of this embrace forces her to twist her lower back, and reach

around with her left leg to step in the direction of travel.

As far as I can see, this embrace is mostly decorative. It has little practical value, but it's popular with academic and stage dancers, because it lets them dance close together, and still display their faces for the camera. It also facilitates the currently fashionable head position, in which the woman places the bridge of her nose saucily against the side of the man's face. And although it makes the woman's back step more difficult, it has an asymmetry that causes her to wiggle her butt as she dances (another of the current fads). This may be okay for flexible young dancers in a short exhibition, but an embrace that causes the woman to continually twist her lower back and reach around awkwardly with every step, isn't going to hold much interest for people who dance every day in milongas.

A Note on Head Position

The position of the head seems like one of the few things in tango that would be easy, but it always seems to give me problems. I'm probably not one to give advice on it, but here's what I do:

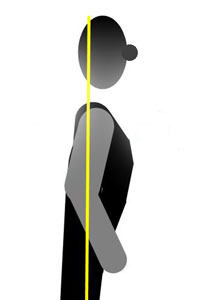

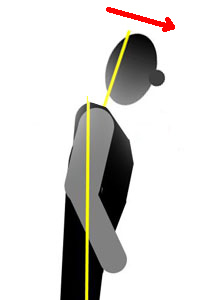

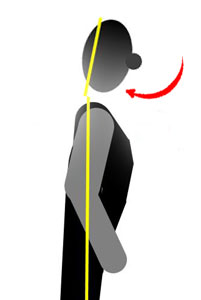

In figure 1, the head is too upright. In fig. 2, it's too far forward and down. In fig. 3, it's just right.

The first figure on the left is the result of using the "string posture" described on page 6. I think it results in a head position that's a little too upright—but you should also avoid tipping the head forward and down, as in figure 2. When you move the head forward, it changes your center of balance. It can also cause you to bring your shoulders forward, and you'll lose some of your chest-forward posture. I think the head position in the last figure is best. (The only changes I made in these figures were to the head. I didn't touch the rest of the image, but it's interesting to note that moving the head makes it appear that there are changes in the posture of the rest of the body as well.)

One way to achieve the ideal head position in figure 3 is to begin with the very upright string posture in the first picture, and, and then place the fingertips of your hands around your ears, like you're holding earphones in place. Now rotate your hands without letting them move forward, so that your head rotates a bit, and your forehead tips down. Your chin will move in a little, and your head may move forward very slightly—but not enough to affect your posture or center of balance. Instead of your eyes gazing directly forward into the tables, your gaze will be a little downward, maybe at spot on the floor about 20 feet in front of you. This is a good place to be looking in a milonga, both for navigation, and for avoiding the distraction of continually gazing into the eyes of people sitting at the tables.

Finally, remember that the drawn figures in this chapter are basically stick figures. They’re okay for demonstrating things—but they’re stiff. Use them to find the right positions, but then it’s important to relax. Note how Fino & Teresa, and Napo & Lili, in the photos above have the same body positions we've demonstrated in the drawings, but they also have a natural, relaxed posture that allows them to stand and move with minimal effort.

This discussion about the embrace illustrates a basic divide in tango philosophy. Academic dancers generally look at tango as a search for physical creativity and styles that are visually interesting, while milongueros see tango simply as a way of expressing and sharing their musical passion. It's obvious which camp I'm in, but either way, the important thing is to be able to recognize the difference.