The “Cabeceo”

“Cabeza” means “head” in Spanish, and “cabeceo” is the castellano word that refers to the nod of the head that is used to signal the offer and acceptance of dances at a milonga. The cabeceo serves a couple of purposes. First, it minimizes public embarrassment... because it’s a long walk back to the table for a man who has just come all the way across the room and been turned down for a dance. But more importantly, a crowded milonga simply couldn’t function without it. Hundreds of offers and acceptances must fly back and forth across the room each time a new tanda of music begins, and the cabeceo is really the only practical way for everyone to quickly and efficiently find the right partner.

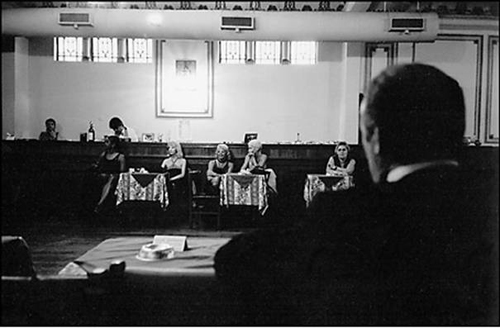

In the milongas of the 1940s, the men often stood in the middle of the dance floor and looked for dances with the young women who were usually seated around the edge of the room with members of their family. (I know this because I’ve talked to milongueras who attended these milongas). In this situation, continually walking from the center of the floor, across the line of dance to invite ladies to dance would have been impossible, so the cabeceo was the only option. Could this have been the birth of the custom? I’ve never heard it discussed, but it seems possible. Today, no one stands in the middle of the floor anymore, but in most popular milongas the tables are jammed together very closely, and there is barely enough room to get on and off of the dance floor, so it makes very good sense that offers and acceptances should be signaled from a distance.

“The Cabeceo” A great picture by Tom Gettelfinger of Memphis

Because I spend most of my time dancing with my wife Alejandra, I’m not especially good at the cabeceo. But she is a master of it, and she asked me to discuss it here. So here is a story. It wanders around a bit, but in the end it should put the art of the cabeceo in perspective, and also say some things about the mysterious codigos of tango. Then I’ll give some practical tips from Alej on the right way to use the cabeceo.

When I first began to go to the milongas with Alejandra, I kept a very low profile. In some of the out of the way places we danced a lot, but when we went to the high powered afternoon milongas I preferred to sit back and watch. And without realizing it I was observing an unusual phenomenon. Alej would arrive, sit in the front row, and begin to dance. She would dance every tanda with each of the older gentleman sitting in the front row across the room. After three or four hours passed, and she had danced with them all, she would leave. She never waited for dances. At first I thought this was how everyone did it, but after awhile I realized that most of the women sat a lot. Even the best milongueras only danced about half the time, and many only danced a few tandas.

How did she do it? The milongas are governed by a set of codigos that apply to the conduct of both the men, and the women. Our friend Julie Taylor is one of the most knowledgeable people in the world about BsAs tango. She is a professor at Rice University who has studied tango for more than 20 years, she has written the best known book in English about it, and she has been dancing and living in Argentina for most of her life. She's one of very few foreign women (maybe the only one) who are really respected in the milongas... but she and I have a fundamental disagreement about tango. I see the codigos as basically a logical and efficient way to keep order, while she has a slightly more negative view. For her, they are somewhat repressive—especially for women. Our argument on the subject always comes down to two things. First, I tell her, I have never personally felt any repression, and second, if women are so repressed in the milonga, why does Alej always do pretty much whatever she wants? Julie, who has watched her for years, agrees that the rules don’t seem to apply to Alej, and she thinks it’s because of her dancing skills. Some of the milongueros call Alej Flaquita, which means skinny. Others call her La Pluma or Plumita. It means feather… but it’s also a play on words that means a writing pen—so I guess they’re saying that dancing with her is like drawing with a pen. Both names refer to the light way she dances. The milongueros want to do as much as possible with the music, and they value a partner who is “light”.

A couple of pages back I showed El Gallego doing an incredible milonga step where he turns 360 degrees balancing and pivoting on only one foot. To be able to do this unrehearsed on the floor of a milonga is incredible, and he may be the only man in the world who can do it—but I neglected to mention his partner. It was Alej. She hadn’t danced with him for several years, and she hardly dances milonga at all (because I never dance it). Yet she was able to follow his almost imperceptible lead without even thinking about it. How many women in the world would El Gallego even try this step with? One ounce of unbalanced pressure from her and he would have tipped off his foot—but they went completely around, over the course of about 15 seconds, and stayed in the music. That's one reason she danced for years without ever sitting out a tanda. But I think it also may have to do with who she is. Because she’s from the neighborhoods, she grew up around the lunfardo dialect, so she understands it as well as the milongueros. For them, she’s a member of the family—and like a little sister who is a little spoiled, they sometimes let her get away with murder. DJ’s change the music for her, organizers change tables and bend rules so we can film, and she seems to be able to violate the most serious of all rules with impunity.

Make no mistake, beneath the surface a lot of power politics is being played in the milongas, but Alej seems to be able to ignore it. She's not afraid to turn down requests for dances from the most powerful milongueros if she feels like dancing with someone else who is lower in the pecking order, and at times I have seen her walk over to some scary milonguero that I wanted to film, and ask him to dance. I always hold my breath, because this should never be done... especially with one of the heavy hitters. But they always just laugh, shake their heads and grumble a bit about the codigos… and then they dance.

Flash back to about 7 years ago. It’s a weekday afternoon at Lo de Celia’s, and the power players of tango are all there, sitting along the front row on two sides of the dance floor, looking for some serious dancing. The women milongueras line the other two sides. For the milongueros an afternoon milonga is usually followed by dinner, and then a night of less serious tango. For many of them, the milongas at night mean champagne and a chance to kid around and fish for tourists or women—but the most important dancing is often done earlier in the day with dancers like Alej and many of the more accomplished milongueras. 7 years ago Alej was a competitive marathon runner who always got up early to train, so she never went out at night. And I think it became sort of a competition among the milongueros to see who could be the first to get her out for champagne. So around 8 o’clock, after dancing a tanda with each milonguero, Alej gets up to leave. As she passes the row of milongueros near the door, the banter starts:

Milonguero #1: “Mira! La Flaquita is leaving early again! She is breaking my heart!”

Milonguero #2: “Come with us to dinner, and then we will go to Gricel and dance all night!”

Milonguero #3: “She has a lover! She won’t go with us!”

Milonguero #2 “Yes, that’s it. She is going to her lover.”

Alejandra: “You know I don’t go out at night. I have to get up early to run.”

Milonguero #1: “Que loco! You are missing your chance. And you are making a serious violation of the codes!”

Milonguero #4: “Yes! If you dance with us, the codes say you must come and have champagne after.”

Alejandra: “Well, I can’t waste my time hanging out with you lazy guys. I have a busy life. If you want champagne meet me in Palermo at 6am and we’ll drink champagne after we run 10 miles.”

Milonguero #5: “This is a very serious violation! We may have to take action!”

It is at this point that Alejandra utters the words that made her reputation:

Alejandra (imitating Bette Davis): “Well, you have your codigos, and I have mine.”

This is a funny story (and believe it or not three milongueros actually did show up to run with her one morning), but things became much more serious when it became clear to everyone that Alej was with me. I think there were some hurt feelings, and I know now that there were discussions about the situation. While the milongueros sometimes bring foreign women into the group for short periods of time, a gringo dancing with someone of Alej’s status was different. In fact, at one point we were told that the milongueros were talking about “punishing us”. I had no idea what this meant, but we both decided to stay away from tango for a while. Alej came back to the U.S. with me, and when we returned to BsAs, it was apparent that things had been worked out.

Nothing was explicitly said, and at the time I was pretty clueless about it, but looking back, I now see what was happening. Every time we went to a milonga, the ranking milongueros would come over, and hug and kiss both of us. Milongueros don’t usually go to another table to do this, and I thought, boy, suddenly everyone is really friendly! I can still remember standing on the floor of a crowded milonga one afternoon shortly after we returned. I was soaked with sweat, and x------ walked into the milonga. He’s a large, powerful man who is important in the BsAs gremios. These are the labor unions that have the power to sometimes bring the city to a standstill. He is a very nice man, but certainly not someone you want to cross. When he saw us, he did something unusual. He immediately walked out onto the crowded floor. He was dressed perfectly in a suit and tie, and despite my protests that I was completely wet, he grabbed me in a bear hug and kissed me on the cheek. In the milongas, everyone sees everything. A message was being sent, and a variation of this was repeated everywhere we went. I think that’s when I really began to love the milongueros and milongueras of Buenos Aires—and my feelings were reciprocated.

Tips for Success With the Cabeceo

An 8-step tutorial from Alejandra Todaro

1. Have a plan and be disciplined. Know ahead of time who you want to dance with for each type of music.

2. Have a fallback position. Pick a second and a third choice ahead of time, and keep them in mind.

3. Try to quickly identify the music of the tanda, and then immediately begin to stare intently at your first choice for that type of music.

4. Do NOT take you eyes off that person, even for one second. (If you have a history, the rest is easy, because he or she will probably already be looking back when they hear the music).

5. If no eye contact is returned, wait a bit. If you sense the person is aware of you, but is looking elsewhere, immediately switch your stare to choice number two, and repeat the process.

6. If eye contact is made, any sign of recognition will work. Among the milongueros and milongueras, this is usually nothing more than a glance of a second or two, or maybe a slight nod, or a cutting of the eyes toward the floor.

7. If you happen to make eye contact by mistake with someone you don’t want to dance with, show no reaction at all, and look away quickly!

8. Once the dance offer has been accepted, both partners should maintain eye contact while the woman remains seated, and the man crosses the floor and stands in front her.

9. Only when you are standing face to face, eye to eye, should the woman get up to dance. (This prevents crossed signals, where the intended partner may be sitting in the line of site, but one or two rows back).

10. When the dance is finished, the man always walks the woman back to her table, and then returns to his own.

Here are the tips in Italian

(You may have noticed that although these tips are from Alejandra, they apply equally to both women and men. While the cabeceo is one of the traditional codigos of tango, it is completely "gender neutral". A woman doesn't need to sit and wait for a man to come over to ask her to dance, because the opportunity to either make or accept offers is exactly the same for both men and women.)

The cabeceo is a powerful tool, but be careful. Once I casually smiled and nodded at a well-dressed milonguero across the room. To my surprise, he appeared a moment later at our table, ready to dance with Alejandra! The codigos are complex, and I had essentially contracted a dance for Alej without either of us even knowing about it. So the wisdom that says everyone sees everything in a milonga is especially applicable here. The milongueros have spent so many years watching each other, that they seem almost telepathic.

****

Now, let’s return to our discussion of the most influential dancers of the last century. We’ve already looked at Petroleo and Todaro. Next, we'll look at the man who was possibly the most influential tango dancer of all.